In 1999, Katie John gathered a host of young people together, most of them descendants, and took them camping at Batzulnetas

Thursday, June 6, 2013 at 11:02PM

Thursday, June 6, 2013 at 11:02PM  During a birch bark class, Gary Galbreath, who just made a canoe, needs a little reassurance, and is about to get it.

During a birch bark class, Gary Galbreath, who just made a canoe, needs a little reassurance, and is about to get it.

In July of 1999, I had a contract with the Rural Alaska Community Action Program (RurAL CAP) to produce Alaska's Village Voices, a tabloid newspaper. Katie John was doing legal battle with the State of Alaska over her right to fish at Batzulnetas, where her family had long fished and had never agreed to give up the right. She was also hosting a culture camp for young people, mostly Ahtna Athabascan but at least one transplanted Iñupiat, too.

I traveled there, took a few pictures and wrote a story. Here, as part of the series I am posting to commemorate the life and accomplishments of Dr. Katie John, is the story, along with some of the pictures:

Although the sun shines brightly on the many-colored tents pitched alongside Tanada Creek at Batzulnetas Camp, the light is dim back in the woods where Katie John kneels on the forest floor with her teenage granddaughter. Mosquitoes buzz about in suffocating numbers, biting at every opportunity. Katie pays these whining pests no attention as she and Angie David busily dig about under the moss with their bare hands, find the spruce roots they are looking for, yank them from the ground and roll them into neat coils.

These will be the threads Angie and other Ahtna Athabascan young people will use to stitch carefully cut sheets of birch bark into baskets and miniature canoes.

Throughout Alaska, Katie John, matriarch of five generations of Ahtna people, is known for her successful legal fight against the United States and the State of Alaska. She fought because she wanted to do what she had done as a child with her parents and siblings – namely, to catch salmon at her childhood home of Batzulnetas. As a result of her victory, the federal government took over the management of fish and game from the State of Alaska in October of 1999, after the Legislature refused to allow Alaskans the opportunity to vote on an amendment to the State constitution to bring it into compliance with a federal law that mandates a subsistence priority for Rural Alaskans.

Moose being smoked as it waits for Katie's students to come and learn from it.

Moose being smoked as it waits for Katie's students to come and learn from it.

Today, in this peaceful, quiet setting, Katie John continues to fight – not for herself but for her grandchildren. “These young kids, they don’t know how we lived,” Katie explains after returning to camp. “They don’t get the chance to learn their own ways. They grow up different than we did, they learn different things, but not how we lived. It is pretty hard for our young people to get back to our ways. Pretty soon, all our ways are going to be gone. Us old people are going to pass on and there is going to be nothing left. There’ll be nothing. They don’t know their own Indian way of life, these young people. They’re just going to be lost, that’s all.”

This is what Katie is fighting for now - to teach the young people the knowledge that long sustained their ancestors living here in the shadows of the great, snowy, Wrangell Mountains. For one week each summer, Katie brings the youth of Mentasta to Batzulnetas, where they learn how to butcher moose, catch salmon in a fishwheel, cut fish, and construct birch bark baskets and canoes.

“When they grow up, they can look back and remember they see all these things at Batzulnetas,” Katie explains.

Angie sits down beside her grandmother. “This is a new experience for me. I’ve never pulled spruce roots before,” Angie says. Then she smiles at Katie. “Look, Grandma! I’m dirty!” Katie smiles back.

Katie and granddaughter Angie David gather spruce roots.

Katie and granddaughter Angie David gather spruce roots.

In May of 1898, when Katie’s mother was young, the people of Batzulnetas had spent winter in the “upriver country” hunting moose. As they were returning, they came upon a white canvas tent pitched at the bottom of a hill. There, they met a man with hair so red that it looked as if he were wearing a red fox-skin hat. The red-headed man gathered up a handful of spruce needles, dropped them to the ground, then pointed to himself. The Ahtna took this to mean that many white people were coming into their country. The red-headed man then invited them to sit, brought out sacks of flour and ate bread with them.

The Alaska Gold Rush had begun.

Katie checks out spruce root braiding of one of her campers.

Katie checks out spruce root braiding of one of her campers.

On October 15, 1915, as recorded by a white trader, Katie became the eighth of ten children born to Charlie and Sarah Sanford. She recalls her childhood life at Batzulnetas as a good one. Her people lived free, unbridled by western law. “We catch all the fish we need. Nobody tell us how many fish we can catch.”

At the end of fishing season, the Sanford family would travel elsewhere in the country. In the mountains they would catch sheep, and in the places where they were abundant, caribou and moose.

Campers cut a moose head, which will be cooked for dinner.

Campers cut a moose head, which will be cooked for dinner.

“In the springtime, we come back here, build our bridge, set up our fish trap. It was lots of work in those days; we work all the time. I like it better. It’s a better life than today. Today, you got to use a car. Anyplace you step out on the land, you got to use sno-go. In those days, we walk, walk, walk, and travel with dogs. We don’t stay in one place. We catch fish, moose, any kind of game – sometimes rabbit, sometimes porcupine. We catch caribou. We wait until they get fat, until they are in good shape. It is all clean game. We live by the land. Nobody tell us, ‘don’t do this, don’t do that.’ Anything we want to do, we do it. We don’t need someone’s law to tell us. We Indians have our own law. Our law is strong. We take care of the animals ourselves. When an animal gets a baby, we don’t bother it.

“We care for the animals, we have to make sure they are in good shape. Sometimes we burn the brush. We make everything new, all new grass for the animals to eat.

“My old days, I like better!”

Gene Henry also grew up at Batzulnetas. At the time, he came every summer to help out at camp.

Gene Henry also grew up at Batzulnetas. At the time, he came every summer to help out at camp.

Katie’s education was all on the land. “I never see one day of school,” she recalls. “I don’t know English words, nothing. When I was 15 years old I never talk one word of English. At 15, I go to work at a mining camp. I clean house, I pick up clothes, I wash clothes, but I don’t know how to get paid.” She soon learned that washing one pair of pants, or one shirt, would bring her 25 cents. She did this on a washboard, but didn’t mind.

“It was easy for me when I work for the whites,” Katie says. “I can’t understand when they talk, so I watch their hands. I learned.” In this way, with no formal instruction, Katie John picked up the English language, which, despite her protests that she can not understand “high English,” she uses quite well.

Angie David cleans moose stomach.

Angie David cleans moose stomach.

By 1942, the Japanese had invaded and occupied parts of Alaska. In that year, Katie recalls, “the Army start up a road. They built a really good road in one summer.” The purpose of that road was to support the military in the fight against Japan, but it also opened up the country to large numbers of non-Native people – including those who recognized neither Indian law nor Indian knowledge.

It was on that road that the game warden who shut down her parents’ fish camp at Batzulnetas traveled.

Camper washes bowl with water from Tanada Creek.

Camper washes bowl with water from Tanada Creek.

“After that law comes all kind of law,” she recalls. “Law, law, law! They tell us, ‘don’t do this… if you do this, you break the law, you go to jail.’ They make us scared. Sometimes we’re starving, we want to get meat, but we can’t; we’re scared. You know how I feel about law? Our people got a good law, right here, but they don’t see our law.”

Emma Northway leads a class in birch bark basketry.

Emma Northway leads a class in birch bark basketry.

Even as this was happening, Katie witnessed something which struck her as both strange and painful. Sport hunters followed the new road into her country. “They shoot a moose and take just the head. When we shoot a moose, we eat everything – even the head, the hoofs, the stomach… everything. We don’t want to see any waste. We take everything but the horns. All they take is the horns, then leave the rest to waste. They just want to shoot an animal. To see this… it hurts.”

Still, Katie had a life to live. She married Fred John, settled down in Mentasta and raised 26 children – 14 of her own and 12 adopted. A friend recalled stopping by Katie’s home to visit. “She was washing all those diapers by hand. She was feeding all those children and the house was clean. It was like an Army camp.”

Katie and Fred John raised their children on the food of the land – moose, caribou, sheep and, of course, salmon – but they had to go elsewhere to catch their fish. In 1964, Katie returned to reclaim the camp at Batzulnetas as a Native allotment, but when she tried to fish there, the State shut her down. The Federal government denied her allotment claim. The family then put a fishwheel in the Slana River.

“Then they make a law you can’t fish in that river either,” Katie recalls. “Crazy laws! They really get crazy with those laws!”

Brittany Patrick doing bead work.

Brittany Patrick doing bead work.

In 1960, the one-year old State of Alaska had closed the entire Copper River drainage system north of the village of Copper Center to salmon fishing. The State did this to insure plenty of salmon for commercial and sport fishers downstream and in Prince William Sound.

The closed area included all of the traditional fishing camps of Katie John and the Upper Ahtna people. Under Alaska law, the only place they could go to catch salmon was down to Chitina.

There, Katie saw tourists catch salmon, cut off the heads, strip out the insides and then discard both. “It makes me sick to see this. We eat the whole fish. They cut the fish and throw half of it in the river! It makes me sick. It hurts us! I don’t know how we hurt white people. I don’t know why they want to make us all outlaws.”

Just as her ancestors had fought for Batzulnetas, so too did Katie. She took the government to court and after a 12 year legal battle, received title to 80 acres at Batzulnetas, inside the boundaries of Wrangell/St. Elias National Park.

Yet near the place where Tanada Creek flows into the Copper River stood a sign: “No subsistence Fishing.” Although Katie’s ownership of Batzulnetas was now recognized, the State still would not let her fish there.

Katie could not understand this. She knew there were plenty of fish in the upper Copper and in Tanada Creek. She knew her people had caught those fish for untold centuries without ever threatening the species. Now people who did not know her country were telling her that if she fished to feed her family, she would endanger the entire salmon population. A game official told her that by the time the salmon which spawned in Tanada Creek reached her camp, they numbered only 2,000. If the population was to survive, each one of those 2,000 must be allowed to pass by and spawn upstream.

Katie’s own observations told her that at least 20,000 to 30,000 salmon came to Batzulnetas each year.

“He don’t believe us,” Katie recalls. “I tell him, ‘I know the country more better than you. You just think you know. I do know.’”

Late in the evening, Katie finds some time to relax a bit.

Late in the evening, Katie finds some time to relax a bit.

In 1980, Congress passed ANILCA and with it the rural subsistence preference. In 1982, Alaska adopted a rural subsistence preference. Yet Katie was still prevented from fishing. Downstream, people flocked from the cities to dipnet at Chitina. Large commercial boats, many from Outside, plied Prince William Sound and hauled in huge catches of Copper River salmon. Whatever the law said about a “rural subsistence preference,” the State was giving sport and commercial fishermen a preference ahead of Katie John.

In 1984, Katie John again went to court – this time to force the State to obey its own law and not interfere with her right to fish at Batzulnetas. She went to the newly opened office of the Native American Rights Fund in Anchorage. There, she met a young Chippewa attorney, brand new to Alaska, by the name of Bob Anderson. In consultation with other attorneys such as NARF’s Lare Aschenbrenner and Bill Caldwell of Alaska Legal Services, Anderson began to research Katie’s case.

“When we read ANILCA, Title VIII, we concluded it must mean that before they can cut off a subsistence user such as Katie John, they must cut off other users first,” Anderson, who is now a consultant to the Alaska Federation of Natives, recalls. “Otherwise, why bother putting the words ‘rural preference’ in the law in the first place?”

NARF hired a biologist to study the fishery. He concluded it could easily support a subsistence operation at Batzulnetas and would not even dent commercial, sport or “personal use” fishing takes.

NARF took this information to the State of Alaska, hoping to cut a deal which would allow Katie to put up a fishwheel and avoid further litigation. The State would not consider it. “They managed everything for the downstream dipnet and commercial fishery,” Anderson says. The battle moved forward.

And so Katie John, a back country Athabascan Elder who had grown up with no formal western education, took on the most knowledgeable, educated and skilled men that the State of Alaska could produce – and she won. Her right to subsistence fish was upheld. Yet, in 1989, in the McDowell case, the Alaska Supreme Court ruled that the State’s “rural priority” violated the common use clause of Alaska’s constitution and thus was illegal. The State dropped the priority and fell out of compliance with ANILCA. As a result, the Federal government took over management of all game on federal lands. The feds denied that they had the responsibility to manage fisheries, claiming that even where they crossed federal lands, the waterways came under state jurisdiction.

Katie John disagreed. She sued to force the federal government to live up to its responsibilities under ANILCA, and to take over management in federal waters.

Katie John hugs her grandson, Emmanuel Baker, at Tanada Creek on his seventh birthday.

Katie John hugs her grandson, Emmanuel Baker, at Tanada Creek on his seventh birthday.

Anderson feels the Alaska Native community could have sent no better warrior than Katie John out to do battle for them.

“Katie John is honest, sincere, really smart and knowledgeable. She really wasn’t interested in picking a fight. She is just a person, living up here, who wanted to live as she always had. She is the clearest case of what Congress had in mind in ANILCA. She has a huge family and has earned everyone’s respect. You can sit with her and she can point out on a map all the places she has used.”

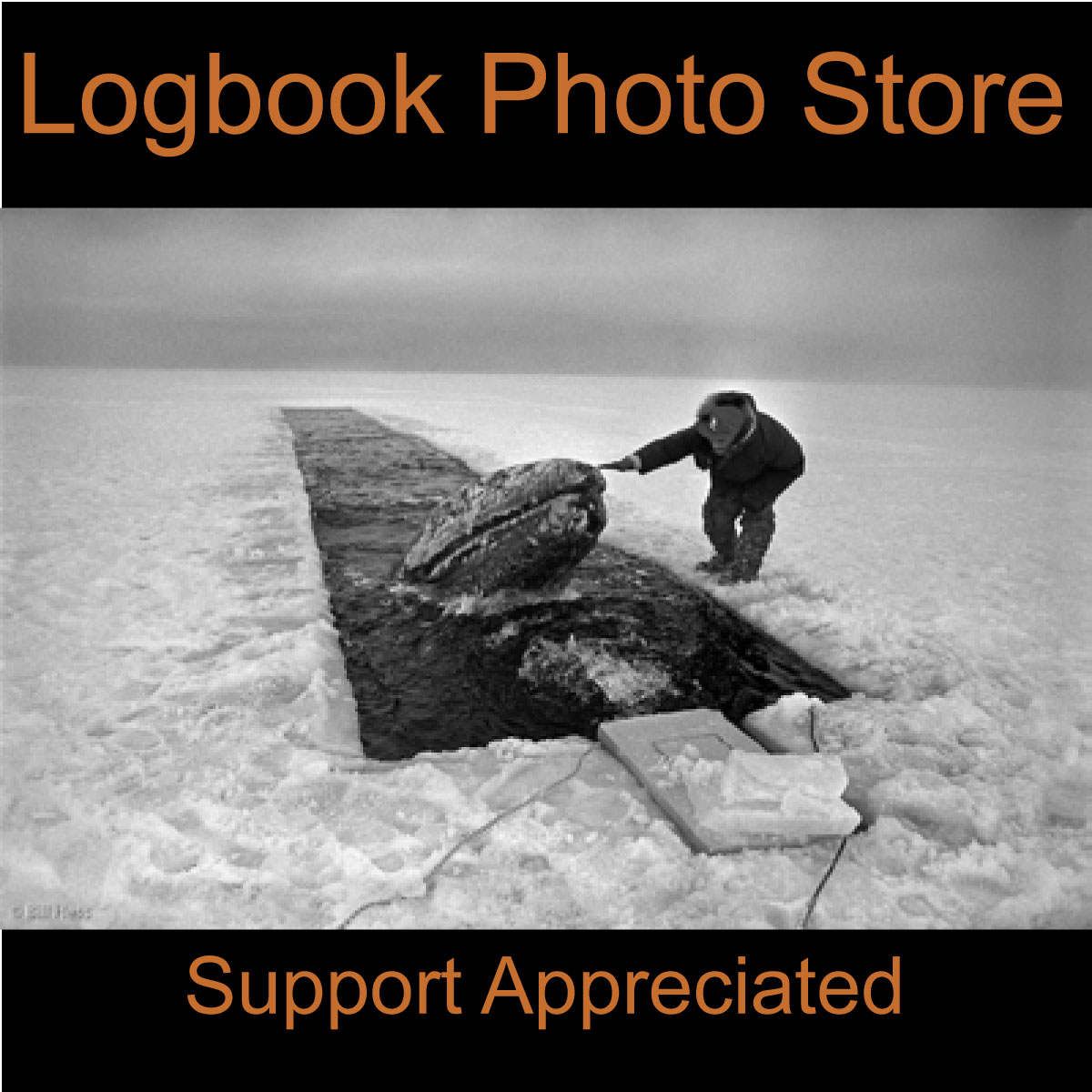

Thanks to Katie John, this fishwheel turns on the Copper River at the village of Chistochina. With her is Bob Anderson, her original NARF attorney. Heather Kendall-Miller had now taken over that roll and would hold it through the remainder of Katie's life. No fish were harvested while I was at camp. In two more posts, fish will be harvested at Batzulnetas.

Thanks to Katie John, this fishwheel turns on the Copper River at the village of Chistochina. With her is Bob Anderson, her original NARF attorney. Heather Kendall-Miller had now taken over that roll and would hold it through the remainder of Katie's life. No fish were harvested while I was at camp. In two more posts, fish will be harvested at Batzulnetas.

Judge Holland ruled in Katie’s favor. “The ruling was sweeping, extending all the way out to the three mile limit.” Anderson notes. In celebration, he joined Katie in taking down the “no subsistence fishing” sign. Yet, the fight was not over. The State appealed.

In 1994, the 9th Circuit Court upheld Holland’s ruling on slightly more narrow grounds. The State petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for a reconsideration of the ruling, but was denied. The federal government had the responsibility to protect subsistence fishing on all waters flowing across federal lands.

Yet, five years later, the federal government has still not taken over management, thanks to the controversial series of moratoriums engineered through “riders” attached to Congressional spending bills by Alaska Senator Ted Stevens. Stevens wanted to give the State the opportunity to amend its Constitution and come into compliance with ANILCA. He did not want the State to lose jurisdiction. Despite polls showing the majority of Alaskans in favor of a rural priority, the legislators refused to allow any ballot measure amending the constitution to move forward.

By 1998, Senator Stevens expressed great frustration with the Alaska Legislature. He warned them that this was their last chance to comply, that there would be no more moratoriums in Congress and that if there was no amendment to bring Alaska into compliance with ANILCA, the consequences would be great. Stevens vowed he would not step in to prevent a federal takeover. The consequence to State management would be devastating, Stevens predicted. Bruce Babbitt, then Secretary of the Interior, warned that even if Stevens went back on this promise and squeezed another moratorium through Congress, he would recommend to President Clinton that he veto it.

Yet, with each moratorium, urban legislators opposing a rural preference became more convinced that in the long run they could overturn ANILCA, either in the Courts or through federal amendments. If they held out long enough, they believed, Clinton would be replaced by a Republican president who would not veto such an amendment.

Then, in a secret meeting closed to any Native participation, Babbitt and Stevens cut a deal for one more moratorium. The State of Alaska was given another year, until October 1, 1999, to put an amendment on the ballot. The State failed to do so and the feds took over management.

In the early days after winning her suit, the family of Katie John felt as if they were being subjected to extra scrutiny by game officials. One summer, Katie’s daughter Nora and her husband Charlie David used a rope and buoy to mark out a swimming hole for the kids in Tanada Creek. Soon, a helicopter landed, depositing an angry game official who demanded that they remove their “net” immediately.

While Katie would like to use a net, “just a ten foot net” she has fished only with a wheel. Even that has come under scrutiny. After posting the registration number prominently on the side, game officials landed at the camp and told the family to post it atop the fishwheel, so that it could more easily be read from passing planes.

Even with her court victories, Katie and her family still feel the loss. For the time span of a full generation, they were denied access to an important part of their life. During this time, they were unable to utilize Batzulnetas and the country of the upper Copper River for subsistence. They were unable to teach the young the skills they needed to know.

“We keep hearing about our victory,” says daughter Nora. “Tell me, what did we win?”

Today, Katie has established what seems to be a good relationship with the National Park Service. Park rangers have come to Katie’s summer camp and held classes with the kids. Once, they dissected “owl pellets” – which the birds cough up much as a cat coughs up a hairball – to see what the owls had been eating. The park service has helped clean up grave sites. It also issues a subsistence moose permit to the camp which assures that the children can learn how to prepare a freshly-killed moose without fear of being arrested by game officials.

Most significantly, the Park Service put up a nearby weir to count the number of salmon passing through Batzulnetas. The surveys took place during two dry years of low water and smaller than average salmon runs. Each time, the Park Service counted in the range of 30,000 fish.

Katie John had been right all along.

Index to full series. * Designates the main, story-telling, posts:

Dr. Katie John, Ahtna Athabascan champion of Native rights before the Supreme Court of the United States: October 15, 1915 - May 31, 2013

July, 2001: Enroute to Batzulnetas to cover historic meeting between Katie John and Governor Tony Knowles; In a couple of hours I will go to Katie John's Anchorage memorial

*Katie John's Anchorage visitation: the void, the continuation

*In 1999, Katie John gathered a host of young people together, most of them descendants, and took them camping at Batzulnetas

I pause this series until after the funeral, but here is Katie John with Governor Tony Knowles and the fish that made the difference

This morning at 4:00 AM - leaving Mentasta after Katie John's funeral and potlatch

*Katie John's funeral and potlatch: on the night before burial, dance wiped away the tears

*Katie John finished well - her descendants mourn, celebrate her life, bury her, eat, dance give gifts and prepare to carry on

One image from Katie John's victory celebration - the story of how she won her victory will soon follow

*Katie John and Tony Knowles at Batzulnetas: a fish escaped, the ice cream was hard and a Governor listened

*When Katie John became Dr. Katie John - closing post